Done in by the State. Did Henry III's government assassinate three senior barons?

Did Hubert de Burgh get away with murder?

As an author of historical thrillers, political thrillers and historical nonfiction, I’m always excited when these subjects overlap. Surprisingly, this happens rather often. So much so that I currently have over twenty unwritten thrillers waiting to be completed!

Usually, such crossovers centre around some form of conspiracy. Some involve a missing link concerning the whereabouts of a lost treasure. Others, the reputed antics of a secret society - or, at the very least, a society with secrets. The most common, of course, is the oldest crime of them all - Murder! Or, when it comes to politics . . .

Assassination.

Recent happenings in the Arctic North have got me thinking. As long as there have been pretenders to the throne or conflicts of interest in politics, there have been dogsbodies on hand to do the dirty work. From Julius Caesar to JFK, there is no shortage of famous leaders cut down before their time. In England, the list of royals who met suspicious ends is astounding. William II, Edward II, Richard II and Henry VI all died in bizarre circumstances - and don’t even get me started on the Princes in the Tower! Thinking about the subject recently, I found myself drawn back to the reign of Henry III, on which I’ve written two major works. To lose one important magnate could be considered unfortunate. Two careless.

Three is just plain suspicious.

One prominent victim of possible foul play in Henry III’s reign was William Longspée, Earl of Salisbury. An illegitimate son of Henry II, Longspée was John’s half-brother and, hence, the young Henry III’s uncle. Famed for his naval antics at Damme in 1213, it has been alleged that John seduced William’s wife after the earl was captured in the aftermath of the Battle of Bouvines (below, Matthew Paris) in 1214, which may have influenced William’s decision to rebel in the First Barons’ War. Regardless of whether there was any truth in the rumours, Longspée later made peace with his young nephew and returned to a degree of influence.

On 23 March 1225, eight years after the war ended, Longspée joined his younger nephew Richard, the king’s brother and soon-to-be Earl of Cornwall, in setting sail with a sizeable fleet to Poitou to bring what remained of the Angevin Empire to submission. Although the sixteen-year-old Richard took nominal charge, Longspée undoubtedly controlled the expedition. As a reward for acting as Richard’s guardian, Longspée was granted wardship of the lands of the late earl of Norfolk.

Although things in Poitou went well for Richard, Longspée’s early success did not last. The earl contracted an illness on attempting his return to England, forcing him to take refuge on the island of Ré, just off the coast of La Rochelle. On returning home the following spring, he passed away at Salisbury Castle.

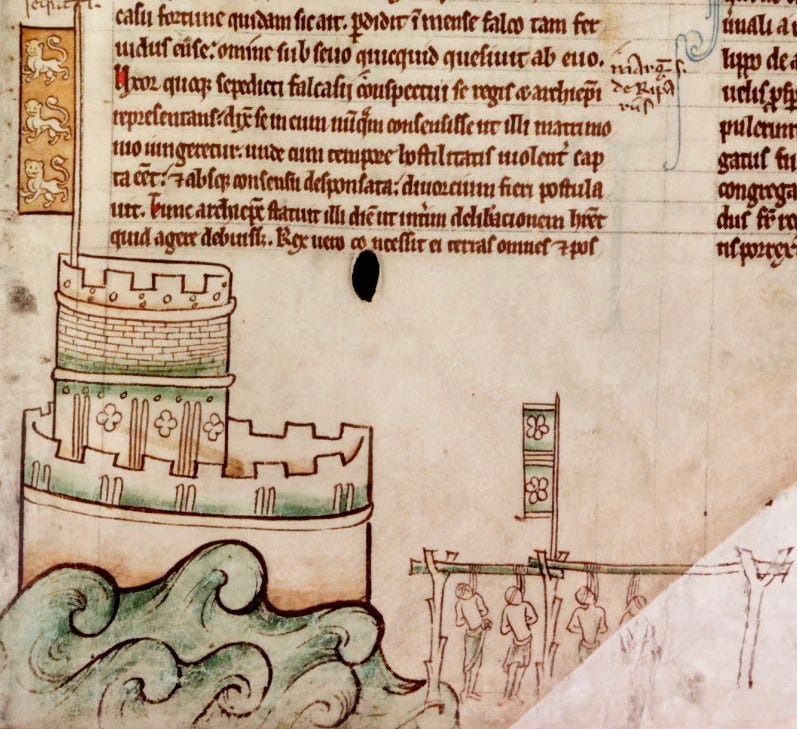

How the earl met his end has long been a point of contention. That his decline was of natural causes in direct connection to his earlier illness is possible. However, the chronicler of St Albans believed he may have been poisoned. The culprit in Roger of Wendover’s eyes was the king’s justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, a talented administrator who had climbed the greasy pole of politics under John before masterminding victory for Henry III at the Battle of Sandwich in 1217 (below, Matthew Paris).

Similar accusations would later be levelled at the justiciar following the death of William Marshal’s eldest son and namesake, William Marshal the Younger, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Born in 1190, William excelled under King John’s care before acting as a surety for Magna Carta. Like Longspée, Marshal took up arms against John and found himself on the opposing side from his father, whom John had appointed Henry III’s regent on his deathbed. Despite their temporary estrangement, there remained much love between the two. After forewarning his son of an impending attack when staying at Worcester Castle, the pair met, ironically along with Longspée, at Knepp Castle before agreeing to take the king’s side. Two years after the war ended, William oversaw his father’s burial and commissioned the greatest knight’s excellent biography, L’Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal, a few years later.

Although it is often difficult to establish the exact nature of medieval working relationships, Hubert and William the Younger appear to have enjoyed solid relations throughout the 1220s. When Henry III, acting on papal advice, demanded his castellans to surrender all royal castles in their control, Hubert cemented his ever-strengthening alliance with Marshal by formally granting him the castles at Cardigan and Carmarthen. Yet, by 1228, any early friendship appears to have been damaged beyond repair. When Henry III and the justiciar attempted to subdue the threat of Welsh rebellion, a lack of financial clout and baronial support left Hubert politically isolated. Complicating things further, William the Younger was now married to the king’s younger sister, Eleanor. For the next three years, relations between Hubert and Marshal remained awkward at best, not least after the justiciar took the blame for the king’s failed military excursion into France.

In April 1231, the plot thickened. Less than a fortnight after the highly anticipated wedding between the king’s brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and William the Younger’s sister, Isabel - then Gilbert de Clare’s widow - William passed unexpectedly aged 41. What caused his death remains unclear. Later conjecture by Roger of Wendover’s famous successor as chronicler of St Albans, Matthew Paris, pointed the finger of blame squarely at Hubert de Burgh through poison.

Another influential player in this bizarre intrigue was the Anglo-Norman soldier Falkes de Breauté. Another to endure a fraught relationship with the justiciar, Falkes’s antics throughout Henry III’s early reign were not entirely devoid of controversy. His refusal to return four manors pawned to him by the regent led to bitter relations with the younger Marshal. A similar dispute arose with Longspée over Lincoln Castle. As fate transpired, Falkes passed away in 1226, two years after being exiled to the continent following his refusal to surrender Bedford Castle, forcing Henry III to resort to siege (below, Matthew Paris). What caused Falkes’s death is another mystery. Writing on Falkes’s demise, Matthew Paris offered two clues. An account of him being found dead after retiring for the night was accompanied by an image of the devil feeding Falkes a fish.

So, what exactly happened to these three influential figures? Regarding Falkes de Breauté, the case against Hubert is flimsy. Although an accusation was made during Hubert’s trial in 1232 following his dismissal as justiciar, much of the noise appears to have been retrospective. No more convincing is the suggestion that Hubert had done similar to the late Archbishop of Canterbury, Richard le Grant, who died in Italy on his way home from Rome.

Regarding William Marshal the Younger, a motive is far more apparent. Not only was William the head of the baronage and married to the king’s younger sister, but his newfound friendship with his double brother-in-law Richard, Earl of Cornwall, was potentially detrimental to Hubert’s dwindling power. While a thirteenth-century man dropping dead at 41 wasn’t unheard of, it does appear to have come as a shock. Despite Wendover having made a similar allegation against the justiciar concerning Longspée, Paris was the only chronicler who made the claim of Marshal, who was interred alongside his father at Temple Church, London. The terrible photo below shows a cast copy of what is believed to be his effigy, then on loan to Temple Church from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Concerning the late earl of Salisbury, the murder case seems far stronger. True enough, Wendover was the only contemporary source to point the finger at Hubert. Yet interesting evidence would come to light in future years. When Longspée’s tomb was opened in 1791, those responsible were shocked to find the well-preserved corpse of a rat inside his skull. Traces of arsenic were also present in the rat.

The question, of course, is why do it? While a motive for killing William Marshal the Younger was political, Hubert’s aggression towards Longspée was likely motivated more by personal embarrassment. During the period when the earl was thought lost at sea, Hubert’s nephew, Reymond, made the bonkers decision to propose marriage to the countess. Not only did Longspée soon turn up alive, but the young Reymond was no noble. When the enraged countess and earl personally took up their grievances with the justiciar, Hubert had no choice but to eat humble pie. Commenting on the matter, Wendover claimed that on apologising to the earl, Hubert ‘invited him to his table, where, it is said, he was secretly poisoned’ (Giles, Wendover, p. 468).

So, what really happened in the dark days of 1226-31? Did Hubert de Burgh really organise three separate murders? While the evidence is patchy, especially for Falkes and le Grant, the possibility that the earls of Salisbury and Pembroke died by dubious means cannot be ruled out. That Hubert was directly involved seems unlikely. Even less likely is that the famously cordial Henry III played any role. On learning of Marshal’s death, Henry furiously wept, ‘Woe, woe is me! Is not the blood of the blessed martyr Thomas fully avenged yet?’

Of all the controversial deaths concerning a ruler’s chief political opponent, the murder of St Thomas Becket undoubtedly takes Alfred the Great’s burnt cake. That Longspée and Marshal were done away with somewhat Becket-style seems more possible, albeit impossible to prove. Even if the king was in the dark, the justiciar had plenty of loyal confidants capable of ridding him of turbulent magnates.

If history teaches us one thing, it is that those in positions of power often have faulty memories, especially regarding things that might incriminate them. At times like this, I find the words of two very different Americans particularly apt. Mark Twain once said, “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” Former US President Ronald Reagan more than once said, “I don’t recall!”

One final call of business. In my previous article, I wrote that I’d be relaxing my Substack schedule from twice a week to a weekly Tuesday. This being Friday, I’m aware I’ve already broken that.

See you next time the muse strikes!