Strange Stories From The Chronicles: Mock Suns, Red Rainbows and Bloody Rain

Did the 13th-century chroniclers really witness multiple suns, monochrome rainbows and rain the colour of blood in England and France?

Further to the stories of blood-red eclipses and multiple moons, as discussed in my last article, the medieval era was chock full of other bizarre sightings. Among the most alluring was one sometimes regarded as a sister of ‘Moondogs’, the far more angelic ‘Sundogs’ (see below, source: Wikipedia).

An example of ‘Sundogs’ may have occurred in England on 8 April 1233. The prominent chronicler of St Albans, Matthew Paris (below), wrote of a strange halo appearing at sunrise and lasting until noon. Intriguingly, a similar occurrence was noted in the Annales Prioratus de Wigornia - the Annals of Worcester. According to the Worcester Annalist, around an hour after the disappearance of that recorded by Paris, people on the borders of Herefordshire and Worcestershire were treated to the sight of a bright semi-circle accompanying an identical halo on either side of the sun. Also present were four red suns and a fifth of the colour of crystal.

Though it’s impossible to know for sure, the chroniclers’ descriptions seem a dead ringer for ‘Sundogs’, also known as Parhelia. Parhelia is an atmospheric condition not dissimilar to ‘Moondogs’ that causes the illusion of one or more bright spots on either side of the sun. Perhaps understandably, the annalist of Worcester viewed the appearance of mock suns and beautiful halos with feelings of hope, not least as the ‘wonderful sight’ happened on Good Friday.

Twenty-one years before this apparent Easter miracle, a bright rainbow was apparently witnessed over the village of Chalgrave in Bedfordshire. In contrast to the typical rainbow, the seven usual hues on this particular April day were blood red. Although such sights are similarly rare, what the chronicler of Dunstable described was almost certainly that of a ‘monochrome rainbow’ (pictured below, source: Wikipedia). Such rainbows occur only when the sun is low, such as sunrise or sunset. Needless to say, the annalist perceived the blood-red arc as a sign of impending doom.

No less concerning to the people of France in 1212 was a shower of blood witnessed on 10 July at Caen in Normandy. Red rain, or blood rain, is more common than ‘Sundogs’ and ‘monochrome rainbows’. Indeed, tales of blood falling as rain go back to Homer’s Iliad in the 8th century BC. The French chronicler Gregory of Tours wrote of such an event over Paris in 582 AD. Likewise, the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth described something similar in his homeland in the 9th century. When blood rain fell over Château Gaillard in Normandy in 1198, the English Augustinian canon William of Newburgh viewed the miraculous sight as emblematic of Richard the Lionheart’s tenacity.

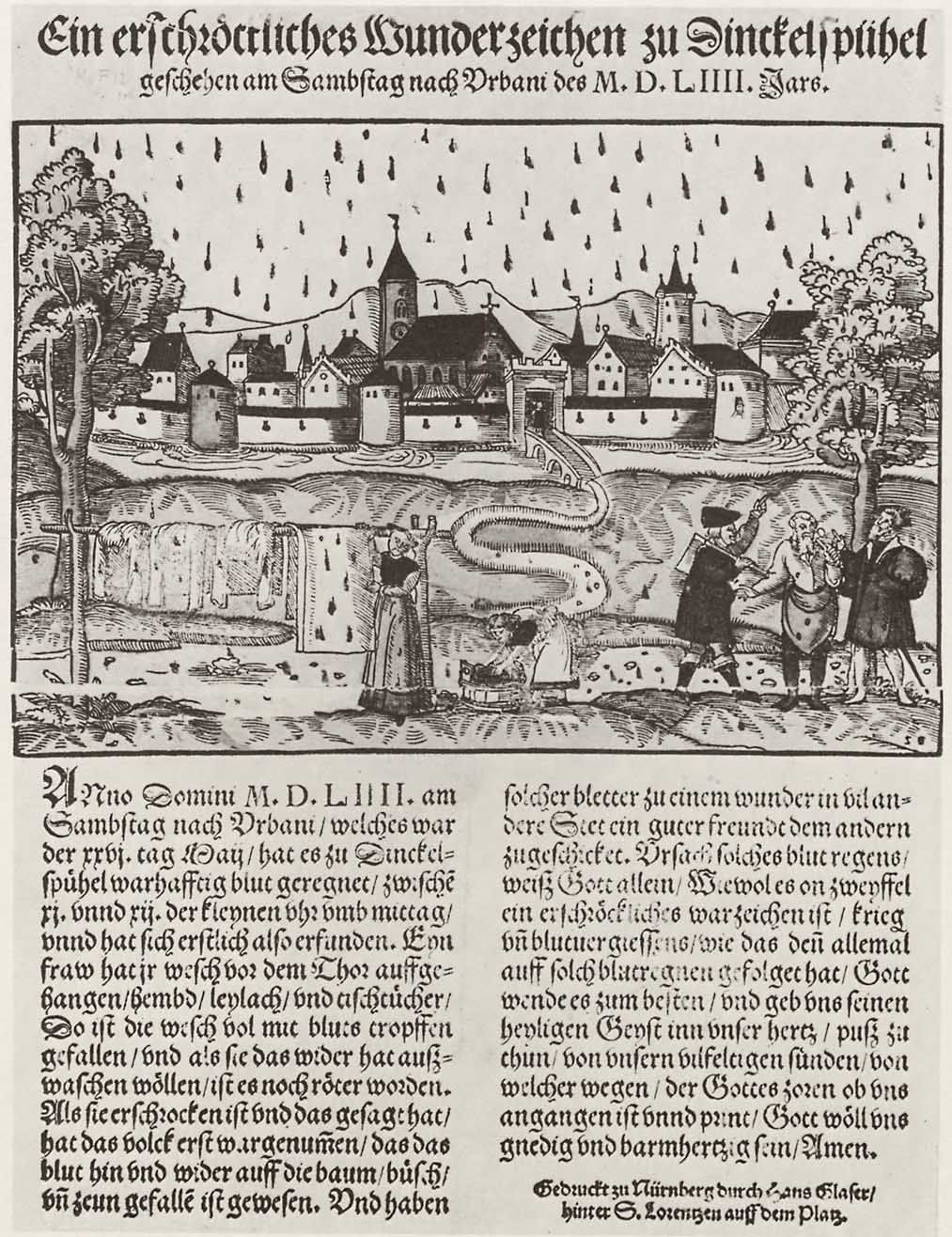

What causes blood rain is still debated. When the German printer Hans Glaser depicted a red shower over the city of Dinkelsbühl in modern-day Bavaria in 1554 (see below), the prevailing mood remained superstition over natural causes. More recently, the Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology (1992) concluded the colour was due to water mixed with dust containing iron oxide. Aerial spores have also been suggested as a possible cause.

Regardless of the strange phenomena’s exact cause, for the people of 13th-century England and France, stories of blood rain understandably aroused feelings of great uncertainty. The fact that the shower at Caen coincided with the alleged apparition of three crosses warring in the sky above Falaise, where John’s nephew, the missing Prince Arthur, had been imprisoned, only furthered the general feeling that trouble was imminent.

As the following months confirmed, 1212 offered no shortage of challenges. As France reeled from the failure of the so-called Children’s Crusade – a bizarre and seemingly spontaneous movement among French youths, which culminated in many being captured by slave traders and sold to the Egyptians – John’s navy wreaked havoc along the Normandy coast before laying waste to the towns of Fécamp and Dieppe. Though John celebrated the excursions’ success, capitulation at Bouvines two years later saw the tide turn. As the eminent Sir J. C. Holt wrote in his celebrated 1961 work, The Northerners, ‘the road from Bouvines to Runnymede was direct, short, and unavoidable’.

The above stories were included in my book, King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War, published by Pen&Sword History.