Tales From The Tower: Samuel Pepys's Treasure Hunt

Does a hoard worth hundreds of thousands remain buried beneath the Tower of London?

Sir Henry Vane, the younger, was executed on 14 June 1662 on Tower Hill. A leading parliamentarian during the interregnum, Vane later fell out with Cromwell over their differing visions and found himself out in the cold after the Lord Protector dissolved the Rump Parliament in 1653. Despite having played no role in the late Charles I’s execution, come the restoration of the monarchy, Vane’s continued fight for reform made him too dangerous a man for the new king to let live.

In attendance at Vane’s grisly end was Samuel Pepys (above), who commented positively on the late politician’s bravery and conduct. At the time, the soon-to-be famed diarist was enjoying a stellar career in the English civil service, working primarily for the naval officer Lord Montagu, created Earl of Sandwich shortly after Charles II’s ascension. A regular visitor to the Tower, Pepys returned four months after Vane’s beheading on Montagu’s orders to investigate a bizarre story involving the previous lieutenant of the Tower, Sir John Barkstead (below). According to rumour among the London underworld, Barkstead had amassed potentially £7,000 in gold coins, which he buried within the walls before fleeing to Germany. How the late colonel had managed this is unclear. Word at the time suggested he had made a nice earning from extorting the Royalist prisoners before stowing away the proceeds in wooden barrels.

So began one of the Tower’s truly unique tales. Inclined to believe the story to be in keeping with Barkstead’s maverick personality, Sandwich sought the king’s permission to conduct a search, which was subsequently delegated to Pepys. Around the end of October 1662, Pepys arrived at the lieutenant’s lodgings, now the King’s House, and presented himself to its famed governor Sir John (Jack) Robinson - later lord mayor of London. Joining Pepys were a Mr Wade and Captain Evett, who circulated the original treasure story on hearing it from one Mary Barkstead, who claimed to be the late colonel’s wife.

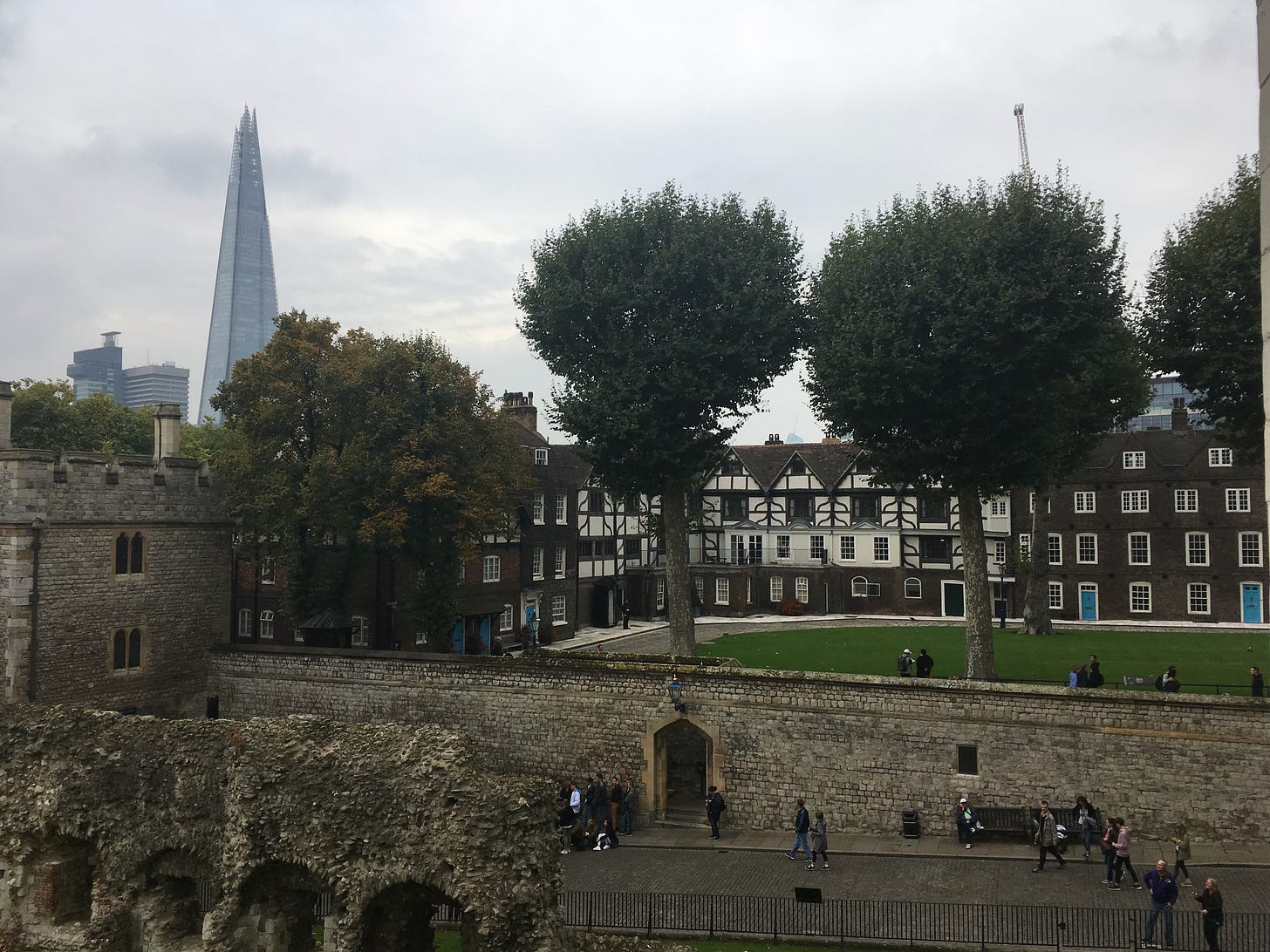

Despite their apparent ignorance over the treasure’s exact hiding place, Mary Barkstead’s referring to a ‘cellar’ within or near the King’s House (as seen below from across Tower Green) led Pepys to an obvious conclusion. The Bell Tower, which dates from the reign of Richard I, adjoins the building and famously includes the same cell in which Sir Thomas More had been incarcerated over a century earlier. No sooner could Pepys say Jack Robinson (kudos to anyone who gets that joke!) did they start to dig.

A disappointing first day was followed by a second. Having become increasingly frustrated at the lack of leads, Pepys adjourned the digging to formulate a more thorough plan. After speaking to Wade and Evett in greater depth, they promised to bring Mary Barkstead to the next session. On 7 November, a third attempt began with the colonel’s alleged widow in their company. Despite her best efforts to remember what her late husband had shown her, the treasure remained unfound, and they left the Bell Tower (as seen below from Water Lane) dejected.

A month passed before a visit from Evett and Wade convinced Pepys to try again. On thinking the matter over, Mary Barkstead concluded that the barrels were actually buried in the garden outside the Bloody Tower - originally known as the Garden Tower (below and to the left). Undeterred by the cold December weather, Pepys gave the green light to a final search. Sadly for all concerned, the result remained the same, and the project was finally abandoned.

So, what are we to conclude? Did the treasure ever exist? Was it found? Does it remain buried? As former Yeoman Warder Geoff (Bud) Abbott concluded, perhaps under a nearby car park? Could somebody have moved the barrels? Was Mary Barkstead cursed by the limitations of a faulty memory? Did the late colonel hoodwink her?

Despite the lack of definitive evidence for the treasure’s existence, the story is not without foundation. Further to the plausibility that the former lieutenant had spent much of the Civil War extorting Royalist prisoners, Barkstead is recorded as having served as a goldsmith in the Strand at the outbreak of the war, which may lend some credence to the possibility of the amassed coins’ existence. The exact value is also subject to some debate. According to the National Archives currency converter, £7,000 could equate to approximately £750,000 in the modern day; however, this discounts its potential historical value. Back then, £7,000 would have been enough to purchase more than a thousand horses, 9,000 sheep, or 10,000 days of trade labour. Not exactly small change.

As fate had it, prior to the treasure hunt, Barkstead had endured a final return to the Tower. He was hanged, drawn and quartered on 19 April 1662, along with two others, for their role in the execution of Charles I. His body was interred, and his head spiked above St Thomas’s Tower (above).

His secrets accompanied him to the grave.

The story of Pepys and his fruitless treasure hunt features in my book, A Hidden History of the Tower of London - England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, published by Pen&Sword History